Trust, Privacy, and Transparency

.png)

Trust, Privacy, and Transparency : An Exploratory Brief

Written by: Mark Nguyen (MBA), Adelina Nie, Morola M (MBAc), Param Patel, Stanley Louie, Saachi Bagde, Rakev Tadesse (J.D.)

Advised by: Anne Marie, Emmanuel Appiah

Edited by: Iain Gabriel, Lauren Klein

Topics: Human Written, Consumer Trust, Privacy, Transparency, Tech, Exploratory Brief

Publishing Date: 1/14/2025 (V1)

Executive Summary:

TLDR: Consumer trust for-profit corporations less than ever before. Declines in trust results of $15Bs+ declines in value, create broad harms to society. The dynamics of trust creation have changed and it is important to consider how it has changed.

KEY IDEAS:

- Trust as market infrastructure: a new lens for companies across brand, product, policy, finance, and communications.

- "Oppenheimer narratives", or fears of one's own inventions (E.g. Open AI) may increase perceived benevolence and trust.

- Trust is increasingly formed bottom up - low trust in media, grassroots community can outweigh top-down institutional messaging.

- Apple’s trust gaps: weak comprehension in privacy policies (low readablity scores), regulatory scrutiny.

- Proactive Transparency can increase trust: real time, adaptive, UX representing how and who is using one's data.

Quality Disclaimer

This is an exploratory brief. The objective of an exploratory brief is, first, to establish bridges across a variety of disciplines on a key issue. Second, it aims to invite discussion and feedback from our partners, community, and clients. It will contain speculation, incomplete arguments, and maybe even grammatical errors. Sos, it should currently be used to inform thinking as much as your favourite restaurant’s seasonal menu should your tax accounting.

Perspectives Disclaimer

Our perspectives may not represent individual writers, nor do they represent the views of their employer(s), and/or associated communities. This is a perspective of the firm, NDR, also operating as ND Research. While the purpose of our practice is to produce useful consumer insights, namely by pulling from a complete set of disciplinary perspectives, tools, and methodologies, we can plainly acknowledge that limitations in our perspectives will always persist. These limitations drive us.

Introduction

Trust. The invisible infrastructure of human cooperation. Long before formal markets or modern states, societies learned that shared belief in one another, not force or resources alone - was what allowed groups to endure, coordinate, and grow beyond survival. Trust, as described by Fukuyama, creates shared norms, which reduce the costs of constant monitoring, enforcement, and contracting [1]. Anthropological research has often treated trust as a precondition for sustained social relations and cooperation [2]. Within contemporary marketing and human behaviour literature, trust is among the most extensively studied predictors of enduring relationships between parties [3]. This makes trust worthwhile for us to think about.

In this exploratory brief, we take up the lens of Consumer Trust and analyze a well loved household name: Apple.

This brief could produce an understanding of the underlying “market system dynamic”, or, the qualities of the marketplace, its actors, how they interact, and how that creates or destroy trust. The objective of this brief is also apply a range of analytical tools to study and contemplate consumer trust. In our analysis we go wide: privacy policies, PR stances, product directions, product marketing campaigns, financial cost and profit estimates, and some legal analysis. Through this broad analysis, we will then suggest several novel approaches that consumer technology brands can use to increase trust.

Trust today

Recently, market research firms have observed a return to increasingly localized (e.g., “glocal”) and individually defined networks of consumption [4, Edelman]. Rather than relying on large organizations or global media, consumer trust is increasingly built from personal connections, community interactions, and shared interests, echoing both familial and neighbourly values. This shift observable in the rise of niche online communities and “micro-influencers,” where smaller creators can be perceived as more authentic and trusted by followers [5, HBR]. This shift potentially represents a more “bottom-up” production of trust that originates from personal needs and interests rather than broad institutional affiliations and symbols. It’s clear that the dynamics of trust have changed.

The “Oppenheimer effect” and surprising consumer trust dynamics…

The invention of the nuclear bomb and the founders’ existential concerns about its potential for mass destruction is surprisingly similar to the narrative pattern of contemporary tech firms today.

“OpenAI’s CEO has publicly acknowledged that advanced AI poses serious risks and that caution is necessary, stating that “we are a little bit scared of this” when discussing the potential negative consequences of powerful AI technologies.” — The Guardian [7]

Statements such as these along with AI safety/alignment research, and governance communities have seeded a novel market system dynamic whereby firms highlight extreme societal risks (such as “existential risks”) of the technologies they are building.

“What we’re building is so important that we are afraid of it.”

This statement is notable for how sharply it departs from decades of traditional risk communication in the technology industry, which has historically been characterized by avoidance (or outright denial) rather than this imaginative scenario. It reflects what we might call a “Oppenheimer effect” - an expression of concern about the unintended consequences of one’s own inventions. These concerns have, in turn, spurred a range of research and governance initiatives that have been highly effective in generating low-cost earned media and public attention. These initiatives are notable, especially in contrast to the broader, long-term decline in institutional trust.

Otherwise, trust remains in systematic decline…

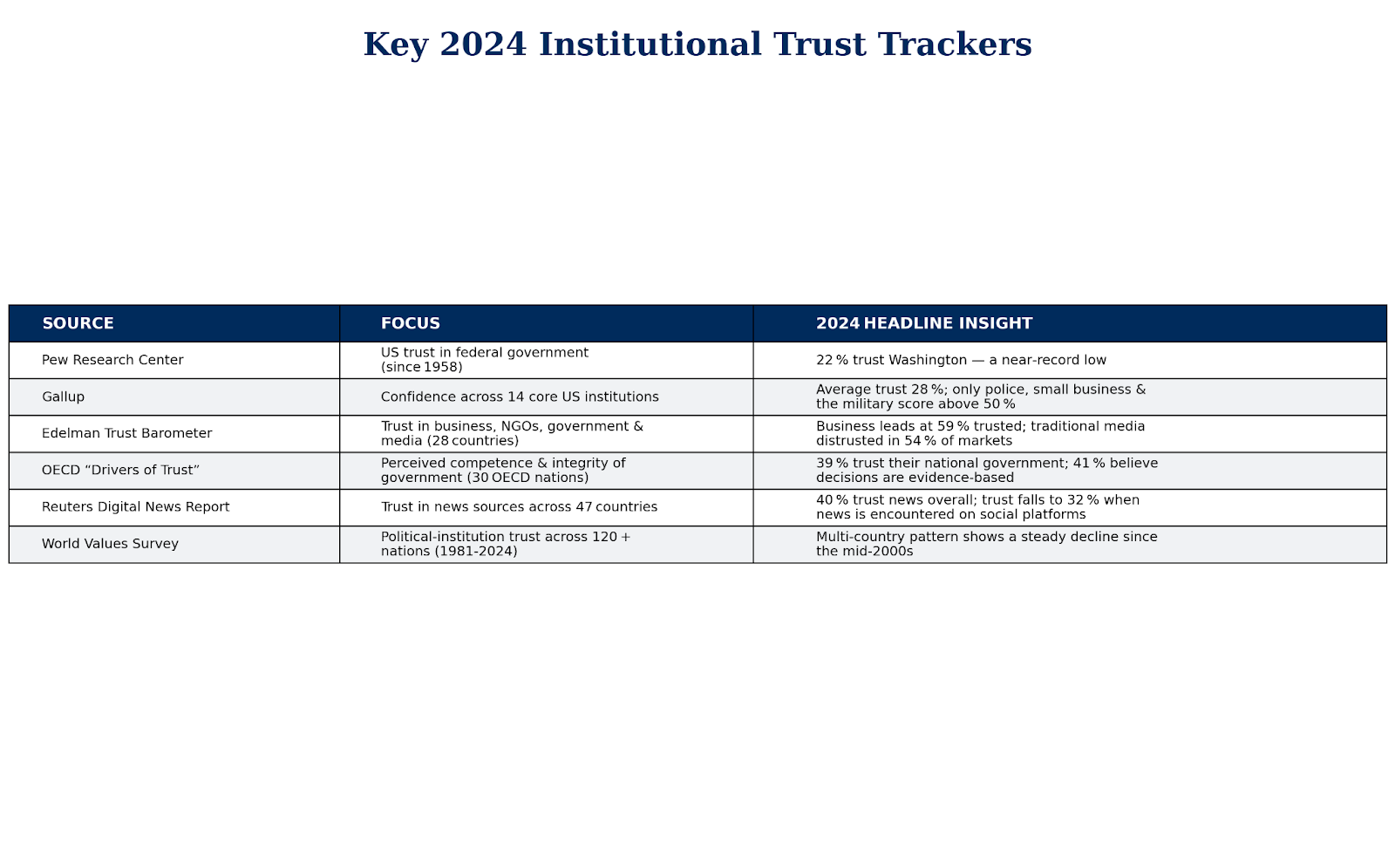

Trust in U.S. institutions has steadily declined over the long run, a pattern documented by decades of surveys from a variety of research organizations [8, Gallup]. Notes from two Pew studies follow:

“A 2024 Pew Research Center survey found that 68% of Americans say large corporations have a negative effect on the way things are going in the country [9, Pew]. Separately, Pew reports that 77% of Americans have little or no trust in leaders of social media companies to publicly admit mistakes and take responsibility for data misuse [10, Pew].”

Measuring the Cost of Lost Trust

30% - estimated median decline in company market value, after a major trust scandal

The Economist’s 2018 study highlights the cost of the loss of trust [11, Economist]

In our research, we were surprised by how widely measured trust is. For such a multifaceted, somewhat abstract concept, there have been many varied attempts to measure trust.

In the quote above, the author measured changes in a firm's market value following consumer trust crises and reported median decline of about ~30% in value. The author provided this medium from a sample set of 15 companies, attributing trust scandals to a total loss of $15B USD in market value. To measure the cost of lost trust, marketing teams have traditionally deployed variety of methods.

Current Industry Practices: Consumer trust has been well measured by marketing teams within corporations, usually as part of a “brand health” dimension. Marketing Research firms like Ipsos, and Kantar may quantify trust changes using several linked measurement systems such as the following:

- brand health trackers (to detect the size/timing of the change in trust)

- driver analyses (to explain why trust moved)

- commercial outcomes (to ultimately link trust to customer WTP)

Within brand health tracking, trust is measured using both direct and proxy indicators. Direct measures include perceived integrity, reliability, and benevolence, while proxy attitudinal metrics such as Net Promoter Score (NPS) and Customer Satisfaction Score (CSAT) are commonly used. These measures are benchmarked against competitors and trended over time to detect shifts in brand perception.

In practice, trust is treated as a leading indicator within broader brand equity and Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) models. Social listening and reputation analytics serve as early-warning signals during periods of reputational risk and are typically linked to downstream commercial outcomes, including retention, churn, and Willingness to Pay (WTP). The effects of these dynamics are clearest when examined through product decisions.

Profits of planned obsolescence (Apple’s phone battery controversy)

We now begin exaimining apple as a case study. While declines in consumer trust are often discussed as reputational risks, they can also be examined through concrete product decisions with clear financial outcomes.

It is well known that Apple introduced a software update in 2016 and 2017 that throttled the performance of iPhones with aging batteries. While Apple framed this as a measure to prevent unexpected shutdowns, many users felt their devices had become slower and less reliable. As a result, people assumed their phones were useless, which led to earlier upgrades [13]. This controversy, later called “Batterygate”, shortened the lifecycle of affected devices and increased replacement purchases, producing short-term financial gains for Apple which we estimate below:

“If performance throttling accelerated upgrades for an estimated 15% of users, the implied shift from a 3-year to 2-year replacement cycle suggests up to ~$50 billion in incremental iPhone revenue during the 2016–2017 period, based on contemporaneous ASPs (~$776)” - Stanley Louie, ND Research

Our Estimation of Profits to Apple for Planned Obsolescence (“Batterygate”) :

See Appendix 1.1 for Assumptions.

Typically, iPhone owners upgrade roughly every three years [18]. With throttling, the cycle dropped to around two years. At an average selling price of $776, this equals to an additional $776 in revenue per user [17]. However, Apple’s $29 battery replacement program in 2018 reversed this trend [16]. Approximately 11 million batteries were replaced that year, compared to the usual 1-2 million. This could suggest that around 9 million upgrades were deferred, delaying $6.9 billion in revenue.

The short-term impact, however, remained huge. Between 2016 and 2017, Apple sold roughly 215 million iPhones per year [15]. Assuming that 15 percent of users upgraded early due to this “throttling”, that results in 64.5 million users or an estimated $50 billion in additional sales [17]. This example shows how seemingly small product decisions can translate into billions of dollars in financial impact. However, decisions like these often come with considerable consequences.

Was Siri Listening? A Legal perspective

Provided by Rakev Tadesse, J.D.

During the Batterygate controversy, Apple agreed to pay up to $500 million to settle related U.S. litigation (without admitting wrongdoing) [27, Business Insider]. This settlement emphasized the potential erosion of consumer confidence when transparency is lacking. This settlement stirred up much social media commotion, leading to a belief that Apple has been intentionally slowing down older iPhones to encourage users to purchase new phones. These legal challenges present to us the financial costs of activities that decrease consumer trust.

Furthermore, Apple has long positioned itself as a product-centric firm rather than a data-monetization platform, emphasizing that its primary revenues derive from hardware sales rather than the extraction or resale of user data. Privacy and consumer trust have accordingly become central elements of Apple’s competitive positioning.

This carefully cultivated identity came under scrutiny following a 2019 Guardian investigation alleging that Apple contractors routinely reviewed Siri recordings, including recordings generated through accidental activations that captured sensitive conversations [20, The Guardian]. The reporting alleged that Siri could be triggered without clear user intent and that a subset of recordings were transmitted to third-party contractors for quality control, at times exposing confidential medical, commercial, or intimate communications. These allegations formed the factual basis of Lopez v. Apple Inc., a consumer class action filed in the Northern District of California, asserting that Apple had violated the Wiretap Act, the Stored Communications Act, and the California Invasion of Privacy Act, alongside a breach of contract based on Apple’s privacy representations [21, Court]. In the end, Apple won the Lawsuit.

From a doctrinal perspective, Apple ultimately prevailed. The Court dismissed the claims primarily on standing grounds, concluding that the named plaintiffs failed to allege a concrete and particularized injury traceable to the specific devices implicated in the Guardian article [22, Court]. Although the Court expressed skepticism regarding the sufficiency of Apple’s consent disclosure - particularly as they related to accidental Siri activation, it nonetheless found itself constrained to dismiss the claims as a matter of constitutional justiciability. The litigation later concluded with an out-of-court settlement in which Apple expressly denied any admission of liability [23, Court].

For instance, last year, the U.S. Department of Justice sued Apple for monopolizing smartphone markets by suppressing competition in areas like digital wallets and messaging apps [25, DOJ]. Such practices could harm potential consumers, leading to overall dissatisfaction in the future. “Similarly, in the European Union, Apple was fined ~$1.95 billion for abusive App Store rules affecting music streaming providers, following a complaint by Spotify [26, European Commission].”

Beyond antitrust and anti-competition issues, Apple has also become quite familiar with privacy-related lawsuits ending in settlements to avoid lengthy trial processes, which can be perceived by consumers as an implicit admission of wrongdoing. In 2025, the company agreed to a $95 million settlement in a class-action lawsuit alleging that its virtual assistant, Siri, recorded users’ conversations without consent (with Apple denying wrongdoing) [24, Reuters].

Legal compliance doesn’t guarantee consumer trust…

Apple’s experience with Siri-related litigation illustrates a recurring dynamic in modern privacy disputes: compliance with legal standards does not necessarily preserve consumer trust. Even when a court rules in a firm's favour, reputational and financial consequences can persist.

Yet the Siri case underscores a structural gap between legal resolution and public perception. Litigation operates as a binary mechanism: claims either survive or are dismissed, liability is either imposed or denied. Consumer trust, by contrast, is cumulative, reputational, and only weakly tethered to judicial outcomes. Even where a firm satisfies statutory requirements and defeats claims on procedural grounds, the narratives generated by privacy controversies may persist in the public imagination, shaping consumer attitudes and market behavior independently of legal findings. The Siri related litigation thus serves as a useful case study in the limits of law as a trust-restoring mechanism by highlighting why, in practice, firms must manage privacy not only as a compliance obligation, but as an economic and reputational asset whose valuation is determined well beyond the courtroom.

Resulting in Apple’s biggest decline in trust

Through our internal analysis of Reddit and Youtube forums on the matter, we have located growing concerns about Apple’s ability to act in the best interests of its consumers [19, ND Research]. In consumer psychology literature, this is known as “perceived integrity”, an important determining factor of trust between parties. Apple's diminishing perceived integrity has unfortunately taken the legal spotlight in the recent decade, where lawsuits against Apple for monopolistic, privacy violating, and manipulative practices have become common.

Signal 1: Softening perceived product quality

Within standard brand health tracking, early signs of declining product quality typically show up as reduced perceptions of reliability and lower upgrade intent, rather than outright brand rejection. In Apple’s case, Business Insider reported in 2025 that consumers are holding onto iPhones longer, citing fewer meaningful performance or quality improvements between generations [18, Business Insider]. From a marketing perspective, this behaviour is a common leading indicator of softening perceived product excellence, with downstream implications for brand equity and customer lifetime value.

Signal 2: Feature–price mismatch

Brand trackers often measure value perceptions through attributes such as “worth the price” and willingness to pay (WTP). Here, Apple has faced growing criticism: the Business Insider study also notes that recent iPhone releases are widely viewed as offering incremental feature upgrades while retaining premium pricing, prompting consumers to question value. Over time, features to price mismatches typically translate to lower upgrade intent and increased price sensitivity, even among historically loyal users.

Despite ongoing global controversy, Apple remains one of the most trusted brands

Despite the loss of trust from the controversies (Batterygate) Apple's brand was largely unaffected. The company has had a history of investment into consumer trust building activities and initiatives throughout its existence, and consistently ranks high in third party trust rankings.

As of 2025, ND Research identified 50+ publicly profiled Apple employees with “trust” in their job titles [19, ND Research]. Apple also describes dedicated privacy engineering and Trust & Safety functions within its organization [31 & 32, Apple]. This labour investment is relatively high vs. competing hardware manufacturers like Samsung, but less than Meta, to which ‘Trust’ denoted Below, we brief 3 programs that furthered apple's progression in this space.

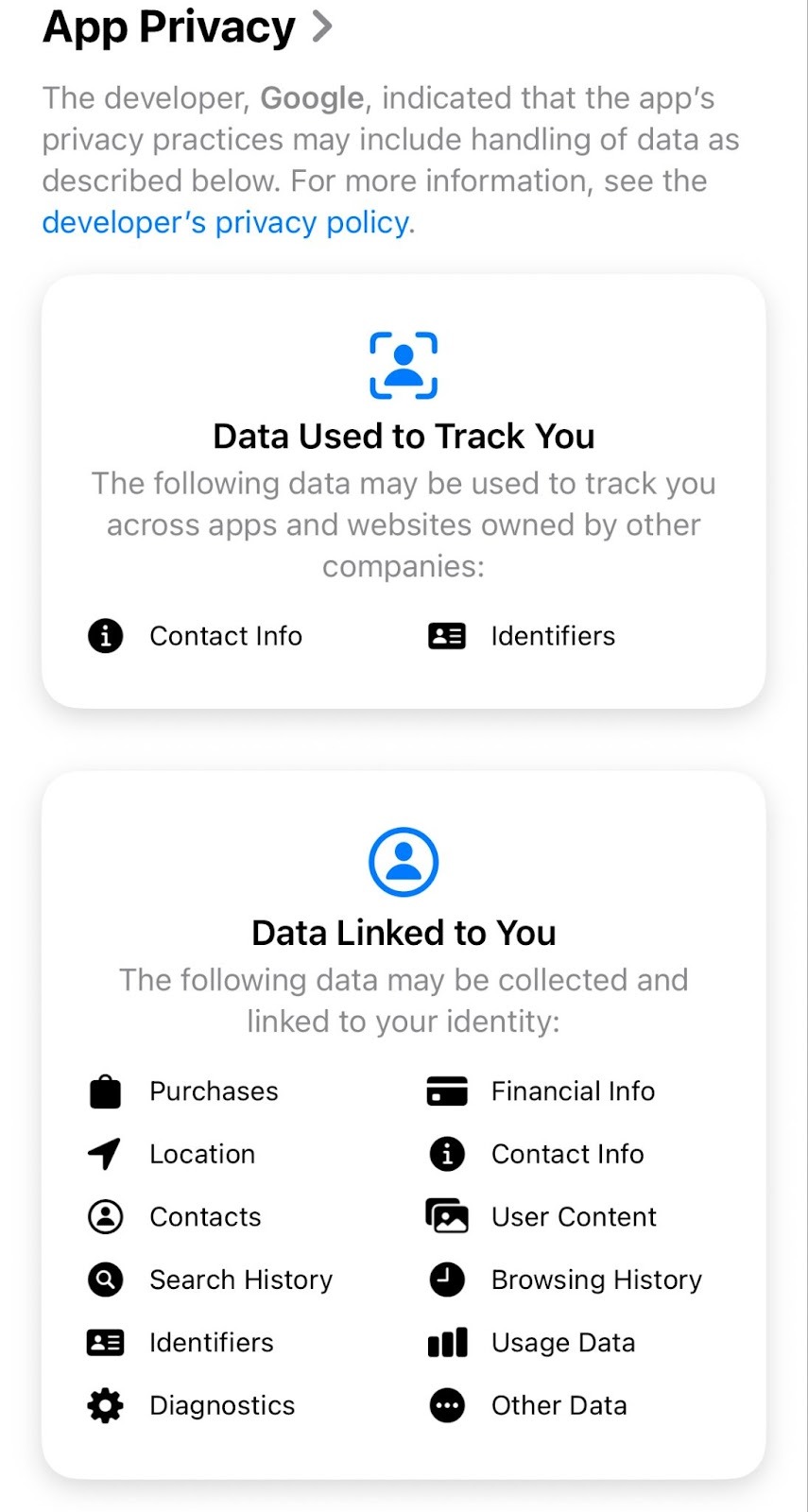

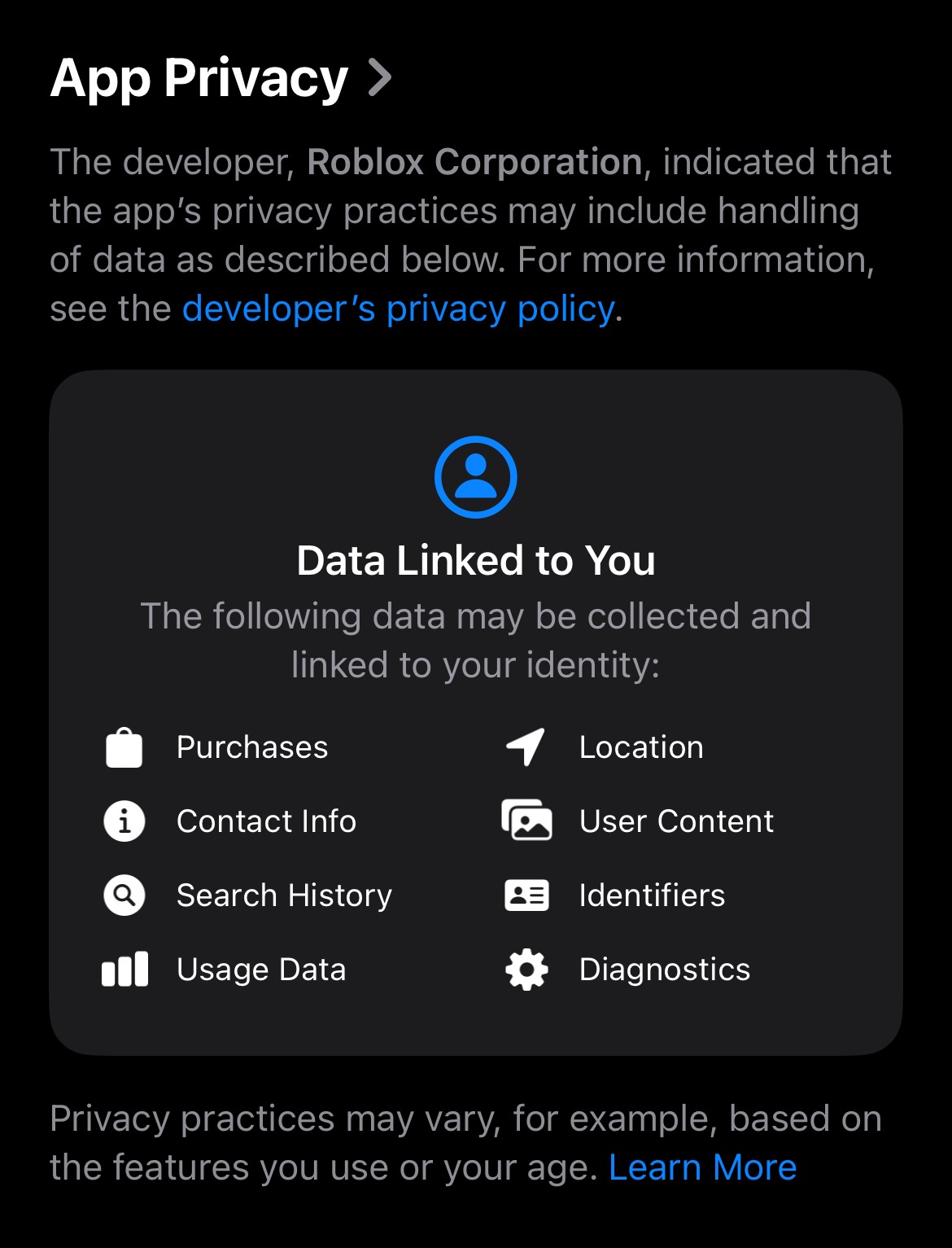

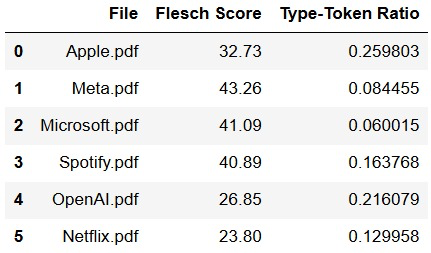

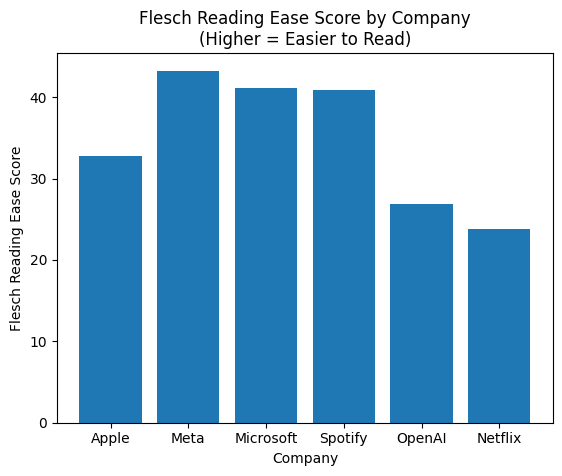

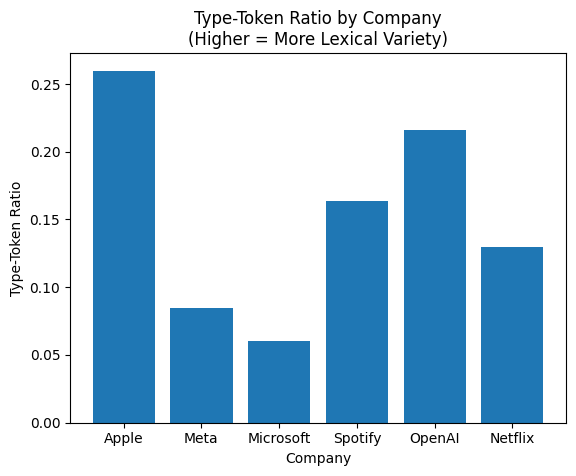

Talking to Users About Privacy: Tech companies need to be clear and upfront about how they collect and use personal data. This means providing privacy policies that are easy to read, transparency reports that actually make sense to regular people, and open communication channels for users to ask questions. Apple's introduction of privacy labels in the App Store, allowing users to know what data different apps collect, was considered innovative at the time of release. However, according to our subsequent analysis, Apple's privacy policies can still be relatively tough to read and understand (compared to other tech firms' policies). Simplifying these documents and making them more user-friendly and perhaps help facilitate more trust.

Privacy Policies and Transparency Reports: Apple regularly publishes transparency reports that detail government data requests and privacy policies. While this is a differentiated activity, users may not use them as they’re long and technical. Our analysis of the readability of privacy policies ranked Apple as low [19, ND Research].. Our ranking was based on two measures of readability. Apple could make these reports more digestible with simple language, infographics, and interactive summaries. If users can quickly grasp what Apple is doing to protect their data, they may trust the company more.

Open Communication Channels: Apple provides privacy resources, but engagement with users could be improved. Companies like Meta and Google have privacy hubs and interactive tools that let users adjust their settings in real-time. Apple should consider integrating an easy-to-use privacy assistant within its ecosystem, (perhaps Siri) to help users manage their settings and understand their privacy options.

How does Apple compare to its peers?

We compare Apple’s transparency and privacy focuses with Google (Android), Meta, Microsoft, OpenAI, and Anthropic. In our analysis, we compare and contrast against Apple’s direct competitors, primarily as a consumer hardware and cloud services provider, as well as other major technology firms with whom Apple may be grouped with when consumer perceptions are formed. In addition, we have considered the following in our analysis:

- Ease of access to privacy policies: Are they easy to find and navigate?

- Clarity: Are they written in plain language or full of legal jargon?

- User control: How easy is it to change privacy settings?

- Transparency reports: How detailed and frequent are they?

- Public trust: How do consumers perceive each company’s privacy efforts?

The analysis revealed that Apple is strong when it comes to branding itself as privacy-focused, but players such as Google and Microsoft provide better privacy education resources, tools, and dashboards. Also, other competitors’ privacy policies interestingly score higher in terms of readability (by Flesch Scores). Apple could improve its efforts by matching competitors' privacy policies in terms of ease of use and readability.

NDR: Our Recommendations to Apple

- Further the “Privacy First” promotional stance: Apple has built a strong reputation for privacy with recent brand messages. One way to further this tradition is through case studies of how Apple’s privacy protections have helped people who desired discretion the most - and perhaps, through thoughtful explorations of what privacy and autonomy now are in a world where everyday life is increasingly tracked and monetised.

- Demonstrate Real-Time Privacy Protection: Our second recommendation is somewhat novel. We propose a product direction that re-conceptualizes customer data as a fluid, dynamic process rather than a static asset. An example feature: enable users to see how Apple and third parties are actively managing and processing their data in real-time. Interactive features within the iOS could display live encryption processes. The reconceptualization of data as a fluid, dynamic asset. Users are notified in real time upon particular instances of the use of their data by Apple or third parties. Apple’s excellent in-house capabilities in UI/UX design allow it to deliver well on this recommendation.

- Proactive, “Frankenstein Narrative” reporting: As initially presented in this brief, we observed how effective existentialist narratives have been helpful for Open.Ai in generating cost efficient, trust increasing press in the company. While Sam Altman’s grand PR narratives are not what we suggest, Apple may benefit from earnestly pursuing analysis and reporting on low probability, worst case scenarios produced by its offerings.

Privacy remains a critical concern for users on both platforms. Apple positions itself as a privacy-centric company, implementing strict guidelines that limit data collection and enforce transparency. Developers are required to provide detailed privacy labels, informing users about data collection practices. However, studies have found discrepancies between these labels and actual app behaviors, suggesting that some apps collect more data than disclosed. Google has also introduced privacy labels the Google Play Store, aiming to enhance transparency. Despite these efforts, analyses indicate that apps on the Play Store may engage in more extensive data collection compared to their App Store counterparts. A study analyzing over two million apps found that a significant number lacked sufficient privacy policies, raising concerns about user data protection [11, Sensors].

Conclusion:

The consumer trust landscape has shifted. Consumers increasingly hold corporations to higher standards across dimensions such as sustainability, data privacy, transparency, and the social legitimacy of corporate profits amid rising income inequality. As a result, firms must reconceptualize trust not as a static reputational asset, but as a dynamic expectation shaped by evolving social, economic and technological norms.

While new innovative approaches to producing and tending to this trust have emerged, the 3 major factors of consumer trust (according to consumer psychology) remain the same (function, reliability, benevolence). Thus, we continue to encourage companies to focus on the following in product development and marketing efforts:

build valuable products,

build reliable products,

build benevolently.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge the entire team for this wide ranging, year long effort from conceptualization to completion. Thank you Stanley for providing a financial analysis and measurement of trust, edits, and supported by a thorough legal analysis by Rakev. Thank you Saachi for her structuring andframing of the team’s ideas, as well as her work on verifying our sources. We’d also like to thank Emmanuel for providing measures of PR Policy readability to support Adelina's analysis. We would like to also thank Morola for framing PR policies, as well as Param for innovative views on the matter. We’d like to acknowledge the Government of Canada, whose funding supports allow some of this work to happen. Last, thanks to Lauren and Iain for the edits.

Who We Are:

We are a growing consumer behaviour research practice based in Toronto, established in 2019, primarily serving the tech industry. We are focused on discovering strong, resilient consumer insights through a holistic approach to research that fuses rigorous traditional research methods, novel patent pending research systems, as well as PhD level insights from neighbouring disciplines that bring fresh light into critical business concerns. If you’d like to explore how this future will impact you, or partner with us on UX, market, and consumer research and development, reach out to us at mark@nguyendigital.co. Thanks for your evaluation.